For more than a century, both U.S. private industry and tribal corporations have been extracting oil and coal from Navajo Nation (Diné) lands. However, residents still face high poverty rates and low rates of energy access. A new EFI Foundation (EFIF) study examines how environmental justice (EJ) groups near or in areas with energy and industrial development view the efforts of the federal government to mitigate negative effects on communities.

Garry Jay, a Diné member, grew up without running water and electricity in his home, even though there was a power line just off the property. This experience is common. In 2021, 30-40% of homes in the Navajo Nation didn’t have water access, and about 25% did not have electricity.

Meanwhile, Rosalie Speck, another Diné member, both lives without hot water and developed black lung disease after years of cleaning coal dust at a plant near the reservation.

Jay and Speck are just a few of many Diné members—and members of other historically marginalized communities—who have experienced harm without seeing economic growth and empowerment as fossil fuel-driven energy operations and industrial development have grown.

As the United States diversifies its energy mix, will these patterns continue, or will historically marginalized communities have a greater voice and control in the development of clean energy projects chartered within tribal lands? Additionally, how do the EJ organizations that represent these communities view the efforts of not only the government but also various companies to engage with them before building new clean energy projects?

EFI Foundation Study

In recent years, the U.S. federal government has signaled strong interest in exploring clean hydrogen as part of the clean energy transition. The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) has allocated $8 billion to create a national clean hydrogen market through its Regional Clean Hydrogen Hubs (H2Hubs) demonstration program.

The H2Hubs process presents an opportunity to learn from EJ organizations and create open dialogues, leading to a more inclusive approach to clean energy development. To help with this, EFIF published a study to understand the views of EJ organizations and individual members of EJ communities on hydrogen while supporting and facilitating ongoing conversations between policymakers, hub developers, and communities. Here are some of our main findings:

EJ organizations that support “green”—i.e., carbon free—hydrogen see more potential benefits than EJ organizations that do not support any form of hydrogen production.

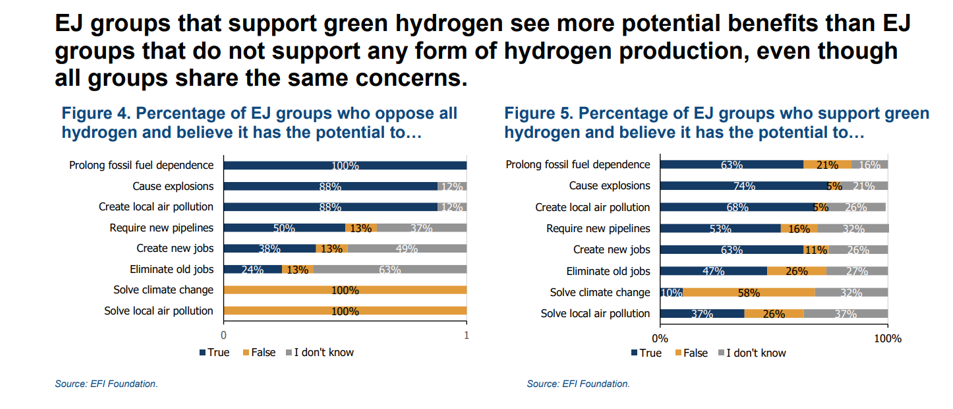

Our survey of EJ organizations showed that some EJ organizations opposed all hydrogen production pathways while other EJ organizations supported the production of hydrogen through electrolysis, which separates the oxygen and hydrogen molecules in water. Hydrogen produced through this method is often called “green” hydrogen because if renewable energy sources are used generate the energy needed to split the water molecule, the hydrogen will be produced without carbon dioxide emissions.

EFIF Director of Research Madeline Schomburg discussed how the two groups of EJ organizations shared similar concerns about hydrogen. Of the group opposing all hydrogen production, 88% said it could cause explosions; 74% of the group supporting green hydrogen said the same. Of the group opposing all hydrogen production, 50% believed it would require new pipelines; 53% of the group supporting green hydrogen believed it would require new pipelines.

However, the organizations that supported green hydrogen were much more likely to cite the benefits of reducing local air pollution and creating jobs than the organizations that opposed all hydrogen production (with a 20-25% gap between the two).

“Support is contingent on production pathway,” Schomburg said at the study release event, which convened speakers from all groups. “It’s not the lack of concern that’s really driving support or opposition but really how you feel about the potential benefit.”

Individual EJ members generally have more positive views on hydrogen than EJ organizations.

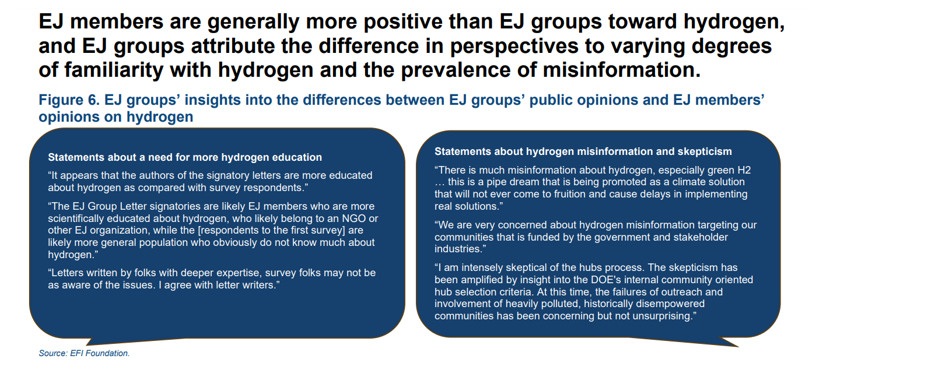

The study found a discrepancy between how individual EJ members and EJ organizations view hydrogen and presented survey respondents with examples of how their views differed. Following that result, the research team asked respondents to reply anonymously to an open-ended question regarding why they believe these differences exist.

From the qualitative data gathered, most respondents attributed the discrepancy to a knowledge gap. For example, one respondent said, “The EJ Letter Group Letter signatories are likely EJ members who are more scientifically educated about hydrogen.” These signatories included EJ organizations and coalitions of EJ organizations such as the Environmental Justice Leadership Forum, who do not view hydrogen as a viable option for achieving an equitable clean energy transition.

Relatedly, other survey responses expressed voiced concerns about “hydrogen misinformation targeting our communities.”

Schombug said that this was a sign that EJ organizations thought that individual members needed more knowledge to make informed decisions about hydrogen.

“It seems that this education component, if you will, is important to a lot of stakeholders in terms of what they see as the main hurdle to helping people understand the issue,” she said.

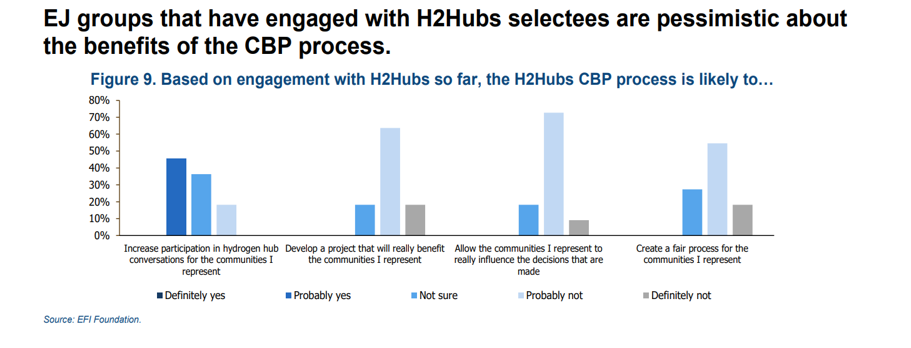

EJ organizations that have engaged with regions selected for H2Hubs funding are pessimistic about DOE’s process for bringing more benefits to their communities.

Our study found that EJ organizations generally did not trust Community Benefits Plans (CBPs), which are part of DOE’s process for ensuring that new energy projects have strong labor and community engagement standards. While they said that CBPs enabled them to participate in more conversations about hydrogen hubs, a majority said that they expected CBPs to not benefit their community, allow their community to influence decision-making, or create a fair process.

“The CBP process may be effectively including more people in the conversation,” Schomburg said, “but perhaps there’s another step [needed].”

She also discussed what the next step in EFIF’s research would be to gain a better understanding of what communities want and need to not only be included, but to be active participants in how H2Hubs projects take shape. A forthcoming EFIF report building on this work will focus on how to create a community benefits agreement.

“We want this next phase of the project to really be community-led,” Schomburg said. “[We want] to ask … if you had access to a group of researchers right now, what do you most want to know? How do you need to be supported to engage? What tangible and intangible things do you need?”

Keep an eye out for the results of this new research. Meanwhile, to learn more about EFIF’s survey results on EJ organizations’ views on hydrogen development in the United States, take a virtual flip through our study (or read the summary on that page), read the summary of our factbook release event, or watch our event recording.

– Madeline Schomburg, Director of Research

– Georgia Lyon, Communications Associate

(Share this post with others.)